- Home

- Penny F. Graham

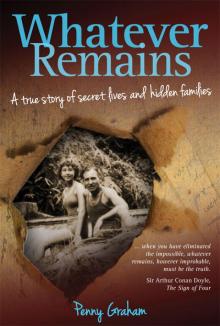

Whatever Remains

Whatever Remains Read online

Copyright © Penny Graham

First published 2015

Copyright remains the property of the authors and apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone: 1300 364 611

Fax: (61 2) 9918 2396

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions

Printed in China by Asia Pacific Offset Ltd

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Graham, Penny F., author.

Title: Whatever remains : a true story of secret lives and hidden families / Penny Graham.

ISBN: 9781925275032 (paperback)

9781925275049 (ebook)

Subjects: Graham, Penny F.

Graham, Penny F.--Family.

Family secrets.

Families.

Dewey Number: 920.720994

For

M. MB, best researcher, best proofreader,

best adviser, best supporter through

the tough times and best friend

and

KC, who encouraged me all the way

How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Sign of Four

In the end, only the truth will do

Contents

Foreword

In the beginning

Part One

Chapter 1 A perfect autumn day, Somerset 1984

Chapter 2 Unravelling the mystery, England 1984

Chapter 3 False stories from the past, 1908–1942

Chapter 4 Just 70 days, 1942

Chapter 5 Last man aboard, 1942

Part Two

Chapter 6 The winds of change, Australia, 1943–1946

Chapter 7 Memories, all mine, England 1949

Chapter 8 The shock of the telling, Australia 1952

Chapter 9 Not wise, nor shrewd enough, 1954–1962

Part Three

Chapter 10 A new city and a new life, Australia 1962–1976

Chapter 11 Return to Canberra, 1976–1987

Chapter 12 A new-found family, 1988–1990

Chapter 13 Daisy’s story, 1920s onwards

Part Four

Chapter 14 Tenacity, 1990–1993

Chapter 15 True stories: England to Singapore, 1905–1926

Chapter 16 Continuing true stories: Singapore to Australia 1926–1942

Chapter 17 Setting the record straight

Part Five

Chapter 18 The other side of the world, 1993

Chapter 19 A pearl in a sapphire sea, 1993

Chapter 20 Pat’s story, 1926–1993

Chapter 21 Cousins

Chapter 22 Nen’s story, 1891–1974

Part Six

Chapter 23 Visitors from England, 1994

Chapter 24 UK and Russia, 1998

Chapter 25 Russia, the first trip, 1998

Chapter 26 Ventures of my choosing, 1999–2006

Chapter 27 Back to Russia, 2006–2007

Chapter 28 A parcel from Russia, 1848 onwards

And at the end

Acknowledgements

Emerson Family chart

Orlov Family chart

Foreword

Penny Graham’s Whatever Remains is one of the most extraordinary books based on historical research it has been my pleasure to read in a career as an historian spanning four decades. Anyone who believes, as historians must, that the past is in one way or another ultimately discoverable from the evidence will surely be astonished and delighted by both the story she tells, and how she tells it.

Whatever Remains is not just an account of the solving of an historical mystery — or, rather, a whole series of them. It is also the story of a woman who, realising that the version of her family history that she had been told could not be true, set about discovering the truth. In that it is a book that demonstrates the importance of historical identity: humans are not just creatures of the moment — our past matters to us.

Penny’s quest became history in three dimensions: in time, of course, but also in space and in that essential dimension of British social history, class. Penny’s research reached back from suburban Canberra to the turmoil of the opening weeks of the Pacific war (she herself must have been the youngest evacuee from Singapore in 1942), but also to the Russian empire almost a century before. Geographically, her search took her to a convent in Malaysia, to rural Britain (where the book begins), and even to Astrakhan in Russian Central Asia. Without giving the story away, she found that the astonishing evidence she uncovered exposes the social history of early 20th century Britain and the possibilities its empire offered for individuals to remake their personal and family backgrounds.

The result is a book that offers an engrossing, exciting and ultimately satisfying account of both who her father was and who he became, and the chronicle of how Penny was able to crack the deception, fantasy and lies she had been given and find both the truth and the family that falsehood had denied, all through painstaking and tenacious research.

Penny’s is an intensely personal story but it resonates far beyond the peculiar circumstances of her background. Historians, and anyone who seeks to understand the human past, ground their endeavours in humanist values, principal among which are a respect for evidence and a desire to use that evidence to reach a justifiable truth, however unpalatable. The book’s title derives from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s words, mouthed by Sherlock Holmes, that after applying a process of logical reasoning ‘whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth’. Not that Conan Doyle, who believed in spiritualism and fairies, necessarily acted upon his own aphorism, but in this case it is abundantly demonstrated through careful historical research that however unlikely it may seem, the story she tells is without doubt verifiable.

Whatever Remains offers a splendid example of a woman who, without any formal historical training (though with the aid of a dedicated husband), set about establishing the truth of her family’s history using little more than the fundamental technique of asking logical questions of a scant documentary record and fragments of (not always reliable) family hearsay. That Penny Graham has succeeded so triumphantly demonstrates both the value of the classic western historical method, but also the power of human familial affection: the desire to know one’s origins and to connect with those to whom we are related.

I commend to you Whatever Remains as one of the most impressive pieces of historical research you are likely to encounter.

Prof. Peter Stanley

University of New South Wales, Canberra

December 2014

In the beginning …

I inherited a history — straightforward, simple even. Many families tweak the truth a little here or there to enhance their family’s past or to pull a veil over the less desirable aspects. My history on the face of it appeared perfectly acceptable, enviable even. As a child, I was given an account of where my past lay, of my family and its traditional British upper middle-class background. As a young adult, I began to progressively question the elements of that neat little history all packaged up and presented to me as the truth of my ancestry. With the passing of time and the surfacing of unexplained events, my disbelief of the so-called facts grew and grew until finding the truth of my family’s past became one of the driving forces

of my life. And so began a voyage of discovery that would last for nearly 40 years.

In February 1942 when the supposedly impenetrable island of Singapore fell to the Japanese army, luck and circumstance brought a young family safely to the shores of Western Australia. This was my family.

The disaster that was the downfall of Singapore presented life-changing opportunities for my father. Opportunities that would give my mother a new nationality and history and would allow my father to shed once and for all of the shackles of a family he no longer wanted.

The canvas of my parents’ lives spreads itself through many countries and over many oceans. Theirs was a world where nothing was necessarily as it seemed and in every twist of fate they saw opportunity. A paradox to the very end, my father took many of the details of his early life with him to his death. To understand the essence of the man was near impossible, for in between the truth of it lay a million possibilities.

Discovering my mother’s true ancestry took me twice around the world to foreign lands whose language and culture belie the mild English-speaking woman my mother appeared to be. The shame of it was that I was never able to really get to know her as she died so very young.

My journey to discover my roots brought together the many twists and turns, false leads and dead ends that led ultimately to a new ancestry and a network of family that stretches far and wide across the world. This story, like all good stories should, unravelled itself in its own good time. Not when I wished, but little by little down the years of my life.

I have held tightly to my fragile strings of memory. Holding on, keeping them safe. Now, with this story I have pulled them together and woven them into the tapestry of my family’s history — adding new facts when they presented themselves, fleshing out old memories and trying to make sense of the past. For to know your past is to know where you belong in the world.

As children, we inherit our traditions, values and many of our ideals from our parents. What we do with them as adults is up to us.

Part One

When I was little, very, very little, and feeling sad, my father could always manage to put a smile on my face by reciting my favourite nursery rhyme; a guaranteed way to have me smiling and happy again. He would hold my small foot in the palm of his long, elegant hand and, tweaking the biggest of my toes, he would begin:

This little piggie went to market …

Chapter 1

A perfect autumn day, Somerset 1984

My mind travels back to a day many years ago, and if I close my eyes I can almost smell the soft rich fragrance of the newly mown fields and the sweetness of the hedgerow flowers, and feel the crunch of the gravel beneath my feet.

Here, in this foreign landscape, is where it all began — the realisation that what I had been told of my family’s history was a sham. The autumn sun sat low over the hedgerows spreading marmalade shadows deep across the road. I was late for the village bus. Running up the hill towards the village store, I saw my Kind Lady with an anxious look on her face, my small suitcase at her side. The bus and I arrived at the same time. She bundled me on, giving me a smile and a squeeze on the arm and a ‘good luck, dear’ as the bus pulled out.

The bus wove through the small country lanes that bordered the patchwork fields of the English countryside. The last rays of the sun stained the dry-stone walls between the fields a warm pink. St Michael’s grey spire grew smaller and smaller as the bus wound its way down the hill. The tip of the spire would be the last thing I saw of that small village in Somerset.

Hot forehead resting on the cool glass window, I watched the village slip away, my warm breath misting the glass. The bus was heading back to Taunton, a large bustling rural town in the County of Somerset where I was to catch the night train back to London.

My journey had been another dead end, another bitter disappointment. Three days ago I had set off from London with such high hopes. This time, I was sure I would find my true identity, my real family, my roots. But I found nothing and the mystery of my family’s origins was to only deepen in this little English village on a perfect autumn day.

Yesterday the bus had brought me to the small village of Milverton. I was here to explore a possible new lead I had uncovered at the Taunton Local History Library the day before. The bus and I parted company at the top of a rise where the green fields of the valley had given way to smallholdings, then an assortment of grey stone cottages, a garage and a small shop.

Imagine if you will, a slim woman of middle height and middle years stepping off that bus alone with her overnight bag and high expectations. Two men worked on a car at the garage, music playing loudly from a small portable radio — the men laughed, heads bent over the open bonnet. They did not look up, so I chose the shop as my starting point.

Opening the door, the smell of an overly full larder — warm and fruity — enveloped me. Shelves of packaged food, jars and tins sat happily side by side with rat traps, boxed candles and packets of matches. It was warm inside, a pleasant change from the sharp morning air.

A pair of smiling eyes and mop of crisply permed grey curls just showed over the top of the counter at the back of the shop. The eyes and curls rose to reveal a compact woman, wrapped firmly in a floral house coat topped with a bright pink cardigan. Much less scary, I thought, than a couple of men in greasy overalls, all testosterone and loud voices.

I asked about overnight accommodation in the village. She soon realised I was not from these parts; in fact, I was an Australian seeking information about her English ancestry. A wife, a mother, and a long way from home — my obvious vulnerability brought out her motherly instincts. She gave me a reassuring smile. ‘The Dutch House takes B&B but you are a bit out of season. But, try them anyhow. No harm in asking, they may well be happy to take your pennies even this late in the season.’

I then and there dubbed her the Kind Lady, and over the next day and a half her kindness and helpfulness sustained me. When I needed a friend to seek advice from or just to talk to, there she was, in her worn easy chair behind the counter. Always ready to talk, a smile on her face, her knitting on her lap.

The ‘Dutch House’, so-called, I assumed, because of the Dutch gable of its roof, was indeed quite happy to take my pennies. The house was well situated just off the main street of the village, large and well maintained with a pleasing view over the valley. My hostess-to-be led me to a pleasant room under the gabled roof. We negotiated more pennies for an evening meal, as the village did not run to a restaurant and ‘the pub don’t do rooms now, nor tea, but you’ll get a good midday dinner there’. So after settling up, I made my way back to the warmth and friendliness of the Kind Lady’s shop.

‘Well,’ she mused, ‘he’s mostly home on a Saturday. Writing his sermon, I should think. Yes, try there first. Even though he’s only new around here he can show you the church register and you can do a walk around the gravestones. But, my dear, I’ve lived here all my life and knows a thing or two about the village and I never heard of that there name you said. But hurry on over there now before they take their midday dinner.’

The church was, as it often is in English villages, on the top of the gentle hill that the village had spread itself around. A few steps up from the road, I passed through the neatly trimmed hedge to the impressive timber gates. The sharp tangy smell of a yew tree mixed with those of damp grass and damp stone. St Michael’s Church, with its warm worn stonework and modest tower, had aged well. Built in the late mediaeval period to withstand the centuries, it was small but solid and well proportioned. This was a building that proclaimed with every piece of rough-cut masonry that it was here to stay.

There was a diminutive but well-maintained graveyard surrounding the church. Many of the older headstones leaned this way and that and, although crumbling and disfigured with lichen and moss, they were still dignified in their state of disrepair. A well-worn path led from the church entrance through a small opening in the hedge to a modest grey stone rectory.

The

door opened. He looked every inch a country vicar — even down to the grey of his baggy cardigan, which harmonised with the stone work of his church. Of middle height and middle appearance, he looked bemused by the sight of me on his doorstep. He also looked compassionate. I sighed with relief — a friendly face.

The vicar of St Michael’s may well have been a new boy to the area, but he was not new to the task of being needed. Patiently accepting of the interruption to his morning’s work, he listened to my ‘abbreviated for strangers’ story. We walked to the church to inspect the church records. These were the days when the parish register could be kept in the church and church doors could be left open. Arson, vandalism and poor box pilfering had not as yet arrived in the village.

Nothing. No names that matched. No baptisms, banns, marriages or burials. No names that matched my name or the name I had discovered at the Taunton Local History Library and considered might be mine. So much for intuition! As the bus rolled into the village that morning, I had had a strong feeling that this was a significant place, a place that, even though I had no memory of it, was somehow important to me and my family. And it would be here that I would begin my final journey.

And so it was to be; only it was to take me another three decades to recognise it.

We sat looking at each other across the time-scarred table, the parish register closed on the table between us. Frustration flooded through me, and the sharp tang of my disappointment hung in the air, mingling with the musty smell of the damp grey walls and worn leather binding of the book lying between us. Caught within a shaft of sunlight from a small high window, dust motes floated by, quiet minutes with them.

Finally, he sighed and patted my hand; a silent comfort. What could he say? ‘Shall we have a walk around the graveyard?’ he suggested. ‘Maybe we will see a name there.’ I think we both knew that this was just a way of breaking the impasse, a way of acknowledging that no matter how carefully we looked through the dog-eared pages, the copperplate script was not going to deliver what I so desperately wanted to see.

Whatever Remains

Whatever Remains