- Home

- Penny F. Graham

Whatever Remains Page 12

Whatever Remains Read online

Page 12

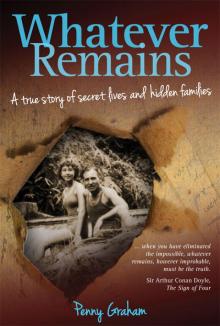

L to R, Irene, Daisy and Nona Brayer, Penang, ca 1932

Julia Brayer (nee Orlova) in her middle years

Karl Gustav Brayer, Julia’s first husband

Nona Brayer, Malaya, age 15

Ernest Arthur Roberts, Julia’s second husband

Daisy Brayer, Singapore, ca 1941

Chapter 12

A new-found family, 1988–1990

Life has a habit of turning up surprises. Call it luck or fate or destiny, call it what you will, but life can change in the blink of an eye or the ring of a telephone and a set of circumstances was about to occur that would culminate in the acquisition of a whole new family and a re-evaluation of the circumstances of my birth.

Back in March 1972, my brother Derek married. He and Anne, his bride-to-be, took a holiday on a plush ocean liner doing a Pacific cruise. When they returned to Canberra some weeks later, they announced that they had been married in Noumea. Who wrote a short article about their marriage in Noumea and how and why that article appeared in the Western Australian edition of one of the country’s most iconic women’s magazines, The Australian Women’s Weekly, is a mystery. But someone did note that the marriage had taken place and the article did find its way to page 10 of the Perth Roundabout section of the society pages.

So, was it luck, fate or destiny that brought me a whole new family? Let’s call it luck. As luck would have it, some time after Derek and Anne’s marriage, one of my soon-to-be found family members in Western Australia spotted the article in an old issue of the magazine. The unusual double-barrelled name of the groom was recognised and a deduction made that he must be one of their long lost cousins. The closing lines of the article announced that ‘She [Anne] and Derek are living in the Canberra suburb of Farrer’.

The article was shown around the family. Discussions took place. There was talk of trying to find us. Family history was regurgitated, old wounds re-opened, old hurts remembered.

My two soon-to-be-known aunts and my grandmother mulled over the prospect of being reunited with Denis, my father, a less than loved brother-in-law and son-in-law and wondered about their half-remembered nephews and niece. Should they try to contact us? Did Nona’s children know they had relatives in Australia? Would Nona’s children want to come back to the family fold? A lot of talking was done, but no action was taken.

Time went by, as time has a habit of doing. My never-to-be-known (by me and my brothers) grandmother died in 1975 and some years later, tragedy struck the family. One of my cousins, Christina, mother of three small children, was diagnosed with leukaemia. Christina’s marriage was falling apart and she appeared to be losing the will to live. She was not responding to treatment and was becoming weaker as the days dragged by. She was hospitalised and bone marrow and platelet transplants, using her sisters Jacky and Trina as donors, were done. The transplants were not successful.

Remembering the Women’s Weekly article, Jacky checked the ACT phone book, saw a listing for Denis’s name and rang him and asked if any of his children were available or could he give her their addresses. Denis told her that all three of his children were overseas and unable to be contacted.

We weren’t, of course; all three of us were at that time living in Canberra.

Jacky had decided to contact Denis to try to reach her cousins. She thought we, as blood relatives, if compatible and willing, may have been able to supply a now desperately ill Christina, with another bone marrow donation. Some months later Christina died. She was 33 years old.

Christina’s death left the family in shock. Contacting Denis or his children was again put on the back burner. Jacky decided to let things lie for a while.

A month later, in January 1989, Jacky wrote to my father, asking him for information about his family. She asked him for the postal addresses of his children, as she had decided that she wanted to make contact with us. He never answered the letter. Nor did he mention to us, his three children, that he had received a letter from his niece.

Jacky was the eldest child of my mother’s sister Daisy. She is strong willed, she is forthright and she had decided that she was not going to be put off a second time. After waiting some weeks for a reply to her letter, she again checked the ACT phone book. There were two listings under our family name. She rang the other name and made contact with my brother Derek. Derek gave her my phone number.

I received a phone call a day or two later. This time it was another of my cousins, Shirley, who rang — she introduced herself and told me who she was. I was flabbergasted; I had never expected to hear from family from my mother’s side. My mother had been dead for over three decades.

I had, Shirley told me, two aunts and five cousins, all living in Perth, Western Australia. My aunts, my mother’s two younger sisters, had apparently not been killed in a bombing raid on London in 1940! That bit of information did not come as too much of a surprise as I had thought it very convenient to have both the sisters and the mother all bombed out of existence in one hit. It was the next bit of news that turned my life upside down.

The aunts and my mother, said Shirley, were not English, and had never lived in the village of Milverton in England. The three sisters were Russian, my mother, Nonna (who came to be known as Nona), having been born, they believed, in Astrakhan, a city on the Volga River where it flows into the Caspian Sea. Daisy, the second child, was born in Bombay, and Irene, the third child, in Singapore. Our grandmother, Julia Orlova, had also been born in Astrakhan and my grandfather, Gustav Brayer, was, according to Julia, from somewhere in Poland. Julia, Gustav and baby Nona had left Russia in 1918. Over a period of some six years, they had made their way via India to Malaya. I was, it appeared, of Russian or Russian/Polish descent.

No wonder we had drawn a blank every time we tried to locate a birth certificate for my mother! We were never going to find it, however hard we tried, as we had been looking for the wrong name in the wrong country.

Over the next few days, I spoke to both Jacky and Shirley often, and at length. In those conversations, I was told of the abortive letter in January that year and the first phone call to Denis, of my cousin Christina’s death and of the death of my grandmother, Julia, in Perth, in 1975.

They were anxious to reconnect with our side of the family and asked if they could visit me in Canberra. ‘Of course,’ I said. ‘Come as soon as you can.’ I was overjoyed at the opportunity to meet relatives I had no idea existed. After the initial shock of the discovery of my Russian ancestry, I was very keen to find out all I could about this ‘other family’.

Out of the west they came, a veritable horde, a vibrant interesting group of people who have touched and shaped my and my children’s lives to this day. Like manna from heaven, they descended upon us bringing history, family responsibility and a sense of belonging with them. Arriving in the dawn mist in a battered blue Kombi, out they all spilled from the over full, over heating old van. There was Daisy with her partner David, Daisy’s eldest daughter Jacky, Jacky’s partner Padraig, their two young children Georgia and Andrei, and Trina (Jacky’s younger sister) and her two children Jessica and Christina.

After leaving Perth three days ago they had driven across the Nullarbor Plain to Adelaide to collect Trina and her children, then straight through the night to Canberra. It was a hot January in 1989. Travelling across the Nullarbor is a major expedition at the best of times; in high summer it is extreme, as the temperatures can soar to dangerous levels. Exhausted, elated and very excited, they all piled out of the van and into the house.

We looked each other over, seeking family likenesses and mannerisms. With everyone talking at once, it was quite overwhelming. I was a little disappointed that I could not see any marked similarities in our looks. Both cousins and my aunt had a distinctly oriental look. Their eyes slanted ever so slightly up at the corners. I think I was desperate to see a similarity to make the relationship seem more real. From the few photos I had of my mother I knew she, like me, did not have her sister Daisy’s slanting ey

es, though she did have the same sun-kissed olive skin with deep brown eyes.

The first night they spent with us, our guests put on an impromptu ‘concert’. We had an elderly Ronisch steel-framed upright piano that sits, usually in dignified silence, in our combined lounge-dining room. That night it came into its own. Jessica and Christina showed off their very considerable musical abilities and most of the adults sang or clapped along and we all ended up singing and dancing the evening away. So, this is what it is like to be part of an extended family, I thought.

Only two of our children were living at home at that time — our youngest, Jeremy, still a gangling teenager and Tim, our third son. Tim was only with us over the holidays as he was to start university that year and would be moving to university accommodation. It must have been mesmerising for them to suddenly have this group of people — an aunt and cousins — appear in their lives. By now all the boys had become used to the idea that things in our family were not all they seemed and changes could occur at any time. Looking back now I am amazed at the apparent ease with which they adapted to the changes in their family structure.

Over the next two weeks we spent hours sipping cups of tea and talking, and talking and talking! Of course it would be years before I would really feel that I had got to know my new family and had some idea of the lives they had led. Family charts were drawn up on bits of paper and Lindsay was kept very busy scribbling down birth, death and marriage dates. So many facts in such a short time made our heads spin.

But, wouldn’t you know it — there was now another mystery to contend with. Apparently, our mutual grandmother, Julia Orlova, was not very communicative about her past.

With exasperated sighs and lots of rolling of eyes, they explained. Julia was secretive, they said. She didn’t like to answer questions about her parentage, nor would she talk about her early life. Our possibly Polish grandfather had, according to my new family, either died or run off (no-one knew for sure which and Julia wasn’t saying) not long after the youngest daughter Irene was born after Gustav and Julia had arrived in Malaya.

Julia, they told me, had always been vague about her parents, her marriage and her early life in Russia. She had given no reason for leaving Russia or any indication of exactly how, or where, she and Gustav had travelled before their arrival in Malaya in the mid-1920s. When Julia was in her late sixties, her grandchildren, particularly Shirley, would press her to talk about her past life in Russia. There was a realisation that they knew very little of her past and she would not live forever. When Julia felt the questions were getting too personal, or when she was bored or tired of answering them, her face would become impassive, her eyes evasive and her reply, in her still heavily accented voice, would be, ‘For vhy you vant to know these things?’, and she would clam up. Damn; another secretive parent!

During their visit, my brother Derek and his family joined us for a big family picnic by the lake and for some of our evening meals. Tony also came round to our home to meet his new relatives and struck up a particular friendship with Daisy. They were as keen as I to learn as much as possible about our mother’s past.

At the time of their visit, Denis was in hospital undergoing a small medical procedure. I had told him of their intended visit but had had a very uncommunicative response. None of my new family wished to meet Denis at that stage, so I decided to take just Christina, Trina’s youngest, to the hospital to see Denis and introduce him to one of his new-found great-nieces.

As I sat on the visitor’s chair at his bedside with pretty little dark-haired Christina on my lap, he at last asked me who she was, as I had not volunteered her name when I got there. ‘This is Christina, one of Mummy’s sister’s grandchildren,’ I replied. There was a pause, then without a change of expression, he said ‘such a pretty child’ and that was all.

After hearing all that my aunts and cousins had to tell me, I realised I had to completely re-evaluate my mother’s past. How complicit she had been in the deception relating to her British heritage was debatable. I suspect, as the stronger and more forceful of the two, it was Denis who had engineered the change of nationality as he had manipulated so many scenarios of his own life. What a turnabout: from Russian émigré living a hand-to-mouth existence in pre-war Malaya to English gentlewoman in just a few short years. Once again I would need to mentally readjust my understanding of my mother’s complex history. From this point on I will refer to her as Nona, the name she was born with, not Norma the anglicised name Denis gave her.

During our Russian relatives’ visit, my brothers and I were in constant contact. We were all pleased at the opportunity to find out as much as we could about the past on our mother’s side of the family. Denis kept his distance and his own counsel.

Since that first visit, I have made many visits to Perth to meet and get to know my relatives. Knowing them has been a very rewarding experience — they have enriched my life and given me an understanding of a history and background of which I knew nothing. I so deeply regret that I never got to meet my Russian grandmother.

I thought I had forgotten the sound of Nona’s voice. Not surprising as I was only 10 when she died. But when I first met my Aunt Irene and she spoke to me — out of her mouth came the voice of my mother. The soft lilting way she spoke, the timbre and the tone of her voice were all familiar to me. I think if Nona had lived a longer life, these two sisters would have looked alike. Perhaps Nona would be of slighter build, lighter in skin and hair colour and a little taller perhaps, but definitely recognisable as sisters.

Over the years I have built strong relationships with my two aunts, my cousins and their children. Over time, I would ask my aunts and cousins many, many questions — of the time when Nona was a girl, about the grandmother I never knew, of the time when my parents first met. How I would long to fill in the gaps in their stories. The missing bits between their version of events and what Nona would, or could, have told me. So many ifs. If only Nona had not died so young. If only I’d had the opportunity to meet my grandmother. If only Denis had not lied about Nona’s early life. Still so many unknowns, still so many gaps.

One day, some weeks after our visitors had left for WA, in frustration I asked Denis why he had not told us Mother was Russian. His reply stunned me. He said he had no idea that she was anything other than British. And he said it with a straight face!

My grandmother, Julia Orlova, my two aunts told me, was reputedly born in Astrakhan. Reputedly, they said, because it was only on Julia’s rather offhand say-so. She carried no identification prior to World War II: no passport, no birth certificate and no marriage certificate. She was always vague about her childhood and early life, not liking to be questioned. Resenting it, seeing it as an intrusion into her private world.

She admitted to being born in Russia, but became vague if pressed to agree to Astrakhan as being her birthplace. For now, let’s assume Julia, and her family before her, did come from Astrakhan.

Astrakhan is at the base of the Volga River where it spreads its mighty waters across a million different pathways before flowing into the Caspian Sea. The city lies across several islands at the top of the Volga Delta. In my grandmother’s time, the river would have been rich in sturgeon and exotic plants. This fertile area formerly contained the capitals of Khazaria and the Golden Horde. By the 17th century, the city was developed as the Russian gateway to the Orient. Many merchants from Armenia, Persia, India and Khiva settled in the town, giving it a multinational and variegated character.

By the time Julia would have been born at the turn of the 20th century, Astrakhan would have been an important rail junction and a major transhipment centre for oil, fish, grain, and timber.

Within a decade, Russia was to experience the beginnings of a grave political upheaval that would lead to many years of bloodshed and ultimately to the formation of a communist Soviet Union. After several disastrous defeats during World War I, the people’s faith in Tsar Nicholas II was waning and a new and powerful ideological concept wa

s to inflame the hearts and minds of many of the Russian people. A recently returned exile, Vladimir Ilich Lenin, provoked the workers and the disaffected with slogans such as ‘Bread, Peace, and Land’.

In 1917, civil war broke out after the Russian provisional government collapsed and the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party, assumed power. Fighting first broke out in Petrograd (now St Petersburg) and then, sporadically over the next few years, across the length and breadth of the country. The principal fighting occurred between the Bolshevik Red Army, often in temporary alliance with other leftist pro-revolutionary groups, and the forces of the White Army, the loosely allied anti-Bolshevik forces. Although Astrakhan was far from the political intrigue in the capital Moscow, there was still fighting between the factions, pitting neighbour against neighbour, and friend against friend.

By 1918, Julia was a young married woman with a husband and infant daughter; Nona, my mother. I assume that because the political upheaval and warring factions made life for the common person uncomfortable, if not dangerous, the young family decided to leave Russia and try their luck in parts unknown. Before they left, the story went, Julia sewed some gold coins into the baby’s swaddling cloths. Apparently, these coins were all they had in the world. Julia never told her younger daughters why they left Russia but, with an uncertain political future, disruption to commerce, trade and the old way of life, it’s not unreasonable that a young married couple would try to make a better life for themselves somewhere other than their war-torn land.

Julia, the family believed, had married young, and according to information given to Shirley, had a stepmother she did not care for and a wish to better herself and her family away from the influence of her parents and broader family. From the information I had at the time, my best guess was that she had either eloped with her young man and, finding herself with child, had decided to leave the town where she was known, or maybe she had married against her parents’ wishes. As Julia did not seem to have any proof of her early marriage, it was a reasonable assumption that, married or not, she left her place of birth to follow the man she loved.

Whatever Remains

Whatever Remains