- Home

- Penny F. Graham

Whatever Remains Page 14

Whatever Remains Read online

Page 14

When Daisy was in her early seventies and writing her memoirs, she told me all those years later she still found it hard to forgive her mother for the constant separations in her early childhood. Not having ever known my grandmother, I cannot judge whether Julia could have made a bigger effort to keep her children close or if the times and circumstances dictated her decisions.

Penang, 1934

All three children now boarded with the Joachim family. Mrs Joachim was German, Mr Joachim an Armenian Jew. They had three older children who still lived at home, in a large dark and gloomy house on Western Road just outside Georgetown.

Daisy and Irene went back to the Light Street Convent. As a 15-year-old, Nona was too old to return to school. Daisy believed she attended a secretarial college of some sort, or more probably, was working in Georgetown, as Daisy remembers that Nona wore pretty clothes and went into town every morning.

Daisy hated the time that she spent at the Joachims. The father drank too much and had a fearful temper and Daisy was very frightened of him. The older Joachim children were spiteful and unkind and Daisy was deeply unhappy at school. The time she spent with the Joachims was one of the unhappiest periods of Daisy’s young life. She felt betrayed by big sister Nona, who did nothing to shield her from the Joachims, and was angry with her mother for leaving her.

One night, she dreamt that Julia was bending over her calling her name. She woke to find it was not a dream. Julia had come to Penang to tell the girls that Uncle Robbie had died. He ‘succumbed to malaria’ and Julia had brought his body back to Penang for burial. The funeral took place a couple of days later. Julia took the girls to see the body of their stepfather. Daisy was not frightened and saw that Uncle Robbie looked the same in death as he did when they had last seen him at the end of the Christmas holidays. He was buried in the old Western Road Cemetery in Penang. A small unidentified concrete headstone marks his passing.

After the funeral, Julia left Penang and disappeared from the girls’ lives once again. Daisy did not know where she went and life went on as usual for the three girls.

Daisy remembers learning to make and fly kites. Monty, the youngest and the nicest of the Joachims’ children, helped them make the kites and taught them how to fly them. They enjoyed those kite-flying sessions because when they were away from the house, they felt free to run and laugh and play.

Daisy recounts that they were taken to the races some Saturdays and that young men were starting to look at Nona. She was developing into a very pretty young woman. Daisy enjoyed these visits to the races as the three sisters were able to spend time together.

One wonderful day the girls were told that they were leaving Penang to join Julia in KL. Daisy can hardly bear the suspense until they finally board the ferry that will take them off the island. Later, Daisy finds out Julia had not paid the Joachims for their keep for some time and that was why they had to leave.

Kuala Lumpur, mid-1930s

When the three girls got off the ferry at Butterworth on the Malayan peninsula, they caught a train to KL to meet Julia. Daisy remembers she and Irene wore matching blue and white polka dot dresses the day they left the Joachims and she was ecstatic to be leaving.

With the family once again united in KL, a few weeks were spent in a cheap hotel where Daisy overheard Julia and Nona discussing the possibility of sending Daisy and Irene back to St Mary’s as boarders. Daisy was so upset that she ran away and was not found for many hours. When she was discovered, she was crying and hysterical and begged Julia not to send her away. There was no more talk of being sent as boarders to St Mary’s.

The family rented a small house in Perak Road. The house had two bedrooms, a lounge, veranda, a small kitchen and a bathroom with cold running water and a commode. There was a small servant’s room at the back of the house for an amah but the amah that Julia employed was too nervous to sleep away from the house and usually ended up sleeping on the floor in the girls’ room. There was a small garden with some fruit trees. The rent was 15 Malayan ringgits a month.

Julia and Nona were now working at a hairdressing salon run by a Russian woman called Madame Sonya. Daisy describes her as ‘a vile person, an artificial blonde, rather overweight’. She was also, according to Daisy, rude, aggressive, loud and common. Daisy remembers her as being very demonstrative and waved her hands around a great deal when she talked. Over the next few years Daisy’s and Madam Sonya’s lives would cross a few times but no matter how hard Madame Sonya tried to curry favour, Daisy continued to dislike and distrust her.

Daisy remembers the process of having a permanent wave, a long and painful experience. There was no hot running water at the salon, so all hair washing was done with the use of a kettle filled from a tap out the back. The permanent wave machine had long wires that hung down from a metal cap suspended from the ceiling. At the ends of the wires were thin tubes that the hair was wound around. The process took hours and could, if you were unlucky, give you mild electric shocks. Julia tried out a new perm style called ‘the halo look’ on Daisy, who loved her new curly hairstyle and admired herself in any mirror she could find.

The two younger girls attended a local school that was close to the house and the family appeared stable and happy. They were in this house for a little less than two years and Daisy thought it was the happiest time of her childhood. Julia appeared to be coping financially and life seemed pretty good.

Nona was growing up and admirers have started to call at the house. Daisy describes Nona at this time as having clear olive skin, a wide smile, a soft voice and beautiful dark brown eyes.

From photographs my Perth cousins have given me, I can see my mother was indeed an attractive young woman. She was slim, yet curvaceous, with shoulder length wavy hair (or maybe Julia has also given Nona a perm).

Julia was still an attractive woman and Daisy remembers that Julia and Nona often went out together in the evening to dances and parties leaving the younger girls in the care of the amah. Julia confides only in Nona and always in Russian. Daisy was becoming increasingly jealous of her older sister’s ability to speak Russian with their mother and resented their intimate bond. Unfortunately, the close relationship between Julia and Nona was not destined to last.

One day, a tall good-looking man with dark swept back hair (Daisy believes him to be about 30) came on the scene. His name was Denis and he drove a flashy red sports car. At first Denis would take both Julia and Nona out. He took them horse riding, for drives in the country, to dinner, to parties and out dancing. Then he only took Nona. There were many arguments between Julia and Nona. Then, one day, Nona disappeared from the house and their lives. She had run off with Denis in his snazzy red car. There were whispers circulating that Nona was with child.

Denis had not married Nona and Julia believed he was already married. Julia was very angry with Denis and Nona and swore she would never talk to Denis again and told the two girls that they are leaving KL as she has decided to open her own hairdressing salon in Ipoh. Daisy was sad to leave. She was quite happy with her life and did not understand why they had to make a move to another city.

Julia and the two girls left their snug little home on Perak Road and took a train to Ipoh, about 200 kilometres north. Julia rented a run down shop house close to the centre of town. She called her new salon Madam Sonya’s, much to Daisy’s disgust. As Daisy was now the oldest daughter, it was her turn to help in the salon. It was hard menial work and Daisy did not enjoy it.

Daisy’s story ends

It is in Ipoh that we leave Daisy and her story, Fireflies and Scorpions. The remainder of this chapter is based on my recollections of discussions with Daisy and Irene, and on our own research.

Life was not easy for the family. The hairdressing salon in Ipoh failed, Julia moved to Singapore with the two younger girls and they lived in a boarding house run by a Russian family.

Julia went back to work as a hairdresser for her old friend Madame Sonya in her new salon in Orchard Road, Singapore. Daisy

, now 14, started work as a nanny. After a few years she tried office work in Singapore Cold Storage and then, later still, joined the army.

After Nona left, Daisy met up with her on one memorable occasion. When Daisy was about 15 and working as a nanny, she was taken with her two charges to Fraser’s Hill to escape the heat of the lowlands. She met Nona at the guest house where the family was staying. Coincidentally, Nona and Denis were also staying there. Nona had a small child with her, my brother Tony, and was looking tired and unwell. Apparently Tony was a restless baby and a poor sleeper and Nona had not fully recovered from the birth. They talked together all afternoon and it is Daisy’s recollection that Nona not only looked tired, but deeply unhappy as well. I believe that Nona always found childbirth difficult and probably suffered what we now know to be postnatal depression. And she may well have been pregnant again.

By December 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, Daisy, Irene and Julia were all living and working in and around Singapore. Seeing the writing on the wall, Julia had applied for a visa to settle in Australia. Events were to override her decision to emigrate there. By late December, Julia was told that she and her two younger daughters could be evacuated, but they must leave immediately and their destination would be Britain not Australia. They were told to pack just one small suitcase and to be at the dock at Keppel Harbour within the hour. I am eternally grateful that Julia had the forethought to put some family photos in amongst her clothes in her one and only suitcase.

All three managed to get a berth on the American ship West Point, which disembarked her passengers at Colombo, Ceylon. As they were leaving the ship, Japanese bombers began strafing the convoy but, luckily, their ship was not hit. After some weeks in Ceylon, the three found berths on the Empress of Australia bound for London. The convoy was strafed several times during the voyage. When the ship’s sirens went, all the passengers would take cover under the tables in the ship’s dining room. As the ship headed away from the Equator and the weather turned cold, the three found themselves freezing in their light summer-weight clothes. When the ship reached Cape Town, only one member of each family was allowed to go ashore. Julia gave Daisy money to buy warm clothes for them all. They would need those warm coats as England in early spring can be truly bitter. The Empress of Australia docked in Liverpool on 13 April 1942. My grandmother and two aunts were alone in an unfamiliar, cold, war-torn country.

After leaving the ship, they were given very temporary accommodation in Nissan huts erected not far from the wharf. They also experienced their first meal in England — fish and chips. They had never had anything like it before. They all hated the smell and the taste of it.

They spent the next three and a half years in Britain. They were billeted in a small flat in Leeds in West Yorkshire. Julia set up a small one-burner stove in their room, and despite food rationing, concocted mouth-watering dishes that both Irene and Daisy remembered for the rest of their lives. There is nothing like privation to encourage the making of something out of nothing and Julia was very good at that. While Julia did a bit of unofficial hairdressing and needlework, both girls got jobs in a factory making binoculars for the duration of the war.

At the cessation of hostilities, the girls and Julia found their respective ways back home to the warmth and familiarity of Singapore.

By now, my parents had also returned to Singapore. There was some communication between the three siblings, though it seems that Julia and Nona were still not talking to each other. Differences in their ages, circumstances and temperament meant that the three sisters did not maintain a relationship and the two families drifted apart. All communication and contact between Julia, Daisy and Irene and Nona and Denis ceased.

Daisy married Jack Ladbrook in Singapore in 1947. They were to have four children: Jacky, William who tragically died while still an infant, Katrina and finally Christina. Daisy, like her older sister Nona, suffered ill health as she also contracted TB. She had the operation to ‘rest’ her lungs as did Nona. Daisy travelled to Britain to have her operation in a good hospital with world-class doctors. Luckily Daisy’s operation and post-operative care were successful. Unlike Nona, she will have 40 more years to live.

In the late 1960s, Daisy and her husband separated and Daisy migrated to Perth in Western Australia. She took her two youngest children with her to start a new life. Julia had by this time also gone to live in Perth, as had Irene and her family.

When Julia was running a children’s clothing shop in Singapore, she was told that Nona died in Perth in 1952 and that Denis and their three children were now living somewhere in Australia. Julia was grievously hurt that she found out about her eldest daughter’s death through an acquaintance. Her anger and bitterness towards Denis grew as she found he had made no attempt to contact her to tell her of Nona’s death. Even though Julia had been very angry when Nona left to be with Denis, Nona had nevertheless been Julia’s helpmate, confidante and trusted friend through those difficult early years they had spent in Malaya.

Julia had moved to Western Australia around 1963. When Julia first applied for residency in Australia, she was obliged to undergo a chest X-ray and other heath checks. It was discovered that she too had TB. She was hospitalised for some months and given sulphur drugs, but made a good recovery. Even though she had suffered TB for many years, it was not what killed her. She died in 1975 of acute renal failure at the age of 75. She had had a tough life but, by all accounts, she was a tough woman. Uncompromising in her beliefs, thrifty and resourceful, she was clever with her hands, sharp of mind and tongue. She made enemies and friends aplenty, and it is a great pity that I never got to meet her. Unknowingly, both she and I lived in the same city for about a year before I moved to Canberra and she died never having had the opportunity to meet her eldest daughter’s three children.

In 1976, Shirley, one of Julia’s granddaughters, took Julia’s ashes to Penang to be scattered over the grave of her beloved Robbie. Julia has no plaque. One day, several of her granddaughters, including me, will travel together to Penang to give Julia, the very private Julia, a memorial plaque that will have on it the simple facts of her life and death. Even our secretive grandmother, we think, would not object to that.

After her arrival in Australia, Julia never tried to contact Denis even though she had been told that he was living here. Then, while flicking through an old magazine, a family member saw an article about a young man and woman who had just been married in Noumea. The name was recognised and family discussions took place. From a chance encounter with a popular magazine came the knowledge that Julia’s eldest daughter’s husband and her nephew were both living in Australia. They weren’t to know it then but in a few years, this information would be potentially useful for the family.

Part Four

The nursery rhyme that Father was telling me would have me giggling and wiggling by now. When we got to the fourth toe he would say:

And this little piggie had none…

Chapter 14

Tenacity, 1990–1993

The winds of change were once again blowing. The discovery of our Russian relatives now galvanised me into stepping up my search for Denis’s true identity and for any members of his family still living.

Nowadays, my mind was constantly on the prowl, ranging over vast tracts of possibilities. If I could, in the blink of an eye or, as it happened, the ring of the phone, suddenly become half Russian, then who knows what else was possible? Tenacity, I decided, would be my watch word from now on.

My relationship with Denis had by now completely broken down. Not long after the Russian relatives had left Canberra, I had summonsed up the courage to confront him about my mother’s parentage and begged him to tell me the truth about himself. We were speaking on the phone when suddenly the line went dead. He had hung up on me. For the next three years there was virtually no communication from him or from my brothers. My brothers were, it appeared, more his sons than my brothers.

This separation affected the w

hole family. With the arrival of the Russian relatives, I had to ask our sons to mentally rewrite their personal histories. To forget what I had told them of their long dead grandmother and accept a new ancestry, new relatives and a new way of looking at their family’s history.

When, not long after this, Denis and my two brothers withdrew from the everyday life of our family, I had to explain why. The two eldest were particularly hurt. It was very distressing for them to realise their grandfather was so annoyed with me that he was prepared to discontinue his relationship not only with me but with them as well. The hurt I saw in their eyes cut me to the core. Rightly or wrongly, I believed our sons were now at an age when they could cope with the truth, and I told them of the many years that I had been seeking the truth about their grandfather’s identity.

We sat around the dining table and talked of the past and the present, of my trip to Milverton in 1984, of their father’s searching for birth and census records while working in London, of our years of careful enquiry of anyone who knew Denis and of my complete disbelief of his many stories of the past. To speak of the past was easy; to discuss the present was not so easy. Their grandfather had been part of our sons’ lives since we had moved to Canberra and the revelation that I believed he was not who he said he was confused and hurt them. It hurt me too but I realised I had kept my own counsel for too long. Now that they, at least the three eldest, were nearly young men, it was time for honesty.

I now knew with absolute certainty everything I had been told by Denis about Nona was a complete fabrication. She was not English, was not born in a little village in Somerset, did have relatives (lots of them) and her name before marriage was not the very English Norma Briar-Roberts but the Russian Nona Brayer. It would also, I thought, be reasonable to assume that everything I had been told by Denis about his childhood and his family was just as wrong. From now on, I would only believe what we could prove to be the truth.

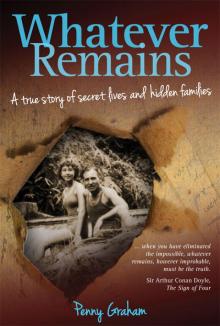

Whatever Remains

Whatever Remains