- Home

- Penny F. Graham

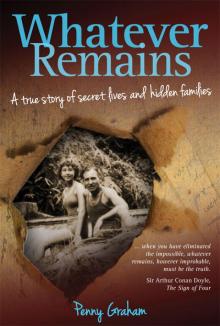

Whatever Remains Page 4

Whatever Remains Read online

Page 4

Photos of this period in his life, shown to me by a cousin some 70 years later, picture him as a gregarious, happy looking young man, often with a bevy of young men and women around him, enjoying the gay social life of pre-war Malaya.

Despite the hard work of his job, he enjoyed to the full the life of a young, unmarried British male. Horse riding, polo, cricket, swimming and sailing — he was proficient in all. He and his friends spent the relative cool of the morning riding or swimming, then home for breakfast and off to work before tiffin (the midday meal prepared by the ever faithful ‘cookie’), with a nap under the cooling ceiling fan during the heat of the afternoon before finishing work for the day as evening approached.

At meal times, an unusual (for someone of European background) aroma drifted from the small kampongs (villages) dotted all over the Malayan peninsula — it was the smell of a mixture of spices, drying fish and blachan, the fermented shrimp paste that is an essential ingredient of Malay cooking. Once you become accustomed to this smell, you never forget it. Denis threw off his eating habits from ‘the Old Country’ and wholeheartedly embraced the new hot, tasty and aromatic dishes of the East.

The heat, humidity and insect-borne diseases took their inevitable toll on Europeans who chose to live and work in the tropics. Most of the larger employers whose staff were from the British Isles sent them ‘home’ for rest and recuperation. These home leaves were for periods of up to three months and were given to employees every two or three years.

During one of Denis’s visits home to England, he met my mother, Norma, at her 15th birthday party. He had been persuaded to join his parents when they visited their neighbours, the Briar-Roberts, to help celebrate the eldest daughter’s birthday. Briar-Roberts, my grandfather, was a rather eccentric man, a coffee broker in London’s Mincing Lane. He was also, so the story went, a cello player of note.

Denis and the other guests were standing in the entrance hall of the Briar-Roberts family home, when he looked up to see Norma coming down the elegant winding staircase in a simple white muslin dress, her golden hair framing her young and pretty face. It was love at first sight for both of them. During the afternoon they talked, getting to know each other. Although she was still only a girl, he fell deeply in love with her that memorable magic afternoon. ‘She was so beautiful,’ he would reminisce, ‘slim and tall with velvet brown eyes and golden curls, her hair put up for the first time to celebrate her approaching womanhood.’ He told us that, some years later, Norma had admitted that, at the end of that memorable night, she had said to her mother, ‘One day, I am going to marry Denis.’ And so she did.

When his leave ended and he returned to Malaya, he wrote often to her with news of his work and life in Malaya. Then, as the years passed, his letters became more ardent. Letters telling of his growing love for her. Three years passed and on his next home leave, when she had turned 18, he finally proposed marriage.

As a child, Norma lived a privileged but sheltered life. Home schooled with her two younger sisters, she was a retiring girl not comfortable in a crowd. Yet, on her 15th birthday, she chose to fall in love with a man 10 years her senior who lived on the other side of the world. What a love story.

What resolve and single-minded devotion she must have had to survive a three-year separation. And, as history revealed, her love did stay true till the end of her short life.

Sadly, Denis explained, Norma’s mother and her two younger sisters died in a bombing raid over London during a shopping expedition in 1940. Norma’s father, my grandfather, had died some years before.

Hmmm, so Norma’s family all died too. After losing your whole family in such tragic circumstances, I thought, it was no wonder my mother had often seemed so sad and quiet. Maybe it was because she felt the loss of her family so deeply, but I never heard her discuss her family or talk of her childhood days in Milverton. Not once, not ever. Her life seemed to begin with her marriage to Denis. Her childhood and family memories remained tucked firmly away, apparently too painful to mention.

Denis would tell of the long lonely days and nights he spent waiting for his future wife to arrive by ship with her parents for their wedding. He had returned to Malaya and his fiancée and her parents were to join him in Singapore where the wedding would take place.

Denis would sit, at the day’s end, on the veranda of his bungalow in the jungle and daydream of the happy times to come when Norma, his bride-to-be, would arrive. Or, with only the company of the small geckos that festooned the walls and the ‘house boy’ clearing up after the evening meal, he would put on his gramophone a recording of ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’ and play it over and over again. He would sit, he would tell us, with a cigarette smouldering between his fingers, a glass of malt whisky at his side, dreaming of his true love whose ship was slowly ploughing its way across the Indian Ocean. He spoke of the relief at her safe arrival, of their marriage at St Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore, of the happy times they had as a young married couple and their joy at the birth of their first born, a son.

In the early days of their marriage, Denis decided the life of a manager on a large rubber plantation was not a suitable existence for a family man. Life could be lonely and isolated, hardly the place to bring up children. They had spent their first few years in the bustling town of Kuala Lumpur (where their first son was born), but now it was time for a change. With a young child and another one on the way, he wanted stability. Always an entrepreneur with an eye to a good business deal, he decided to start his own business importing goods for the ever-growing Asian market and exporting timber, spices and artefacts. The bustling island port of Singapore was the obvious choice.

They set up house in a beautiful home overlooking the sea in a quiet outlying area of Singapore called Changi. Close to the swimming club where the family could relax in the pool or the fan-cooled reading rooms and close to the ocean to take advantage of any cooling night breezes, yet easy commuting distance to the city centre.

By the late 1930s, Singapore had developed into a strong commercial centre and an important trading port. Its city streets were lined with large emporiums and specialty shops selling all kinds of merchandise. The markets and side streets away from the city centre boasted smaller retailers, food shops displaying baskets of multi-coloured lentils, pungent dried fish and aromatic spices, the baskets and boxes of produce spilling out over the pavements to tempt the passer-by. Food stalls and ‘hole in the wall’ restaurants provided the constant crowds with a snack or tasty meal at any time of the day and night.

Their new home was to be Denis’s haven from the busy world of commerce. Where, in the cool of the evenings, he could relax with his family and walk on the lawns that had turned silver in the moonlight. My parents called their home Whitelawns.

After the rugged life of a rubber planter, now was the time to sit back and enjoy the comforts of a well-run home. With his business established and doing well, Denis was comfortably off. He could afford an amah for each of the two children, a cook, gardener, house staff and a driver to take him into the city to and from work. A garden big enough for a pony for the children and stables to allow my parents to indulge their love of riding. Both Denis and Norma had a passion for horses. Rising before dawn, they would ride together in the cool of the morning before the day’s humidity drove them indoors. Then they’d enjoy a substantial breakfast on the wide covered veranda, before Denis would be driven to his work in the city. Norma’s mornings would be spent supervising the household chores or playing with the children.

After an afternoon nap under the cooling fans in the large airy bedroom, there was the option of a late afternoon swim at the Singapore Swimming Club, where Norma would meet Denis on his way home from work. There, European families could relax with gin slings for the adults and lemon squashes or ice-creams for the children. In the cool of the evening, after the children had been put to bed by their respective amahs, a delicious curry or mee dish would be served on the wide veranda to take advantage of the

cooling breeze coming in from the ocean.

On the weekends there were boat trips out to some of the small nearby islands for picnics and Norma learnt to paddle a small canoe so she could take the two little boys for short trips out into the bay from the small beach in front of the house. Tony, their eldest son, was now four years old. Much to Tony’s delight, he was given a Shetland pony called Brown Rascal and allowed to ride around the substantial gardens under the careful guidance of the gardener, Chu Lun. When the tropical heat became too oppressive at Whitelawns, there would be opportunities to spend a few weeks at Fraser’s Hill or in the Cameron Highlands, two hill stations that boasted a cooler climate and lower humidity. There were comfortable guesthouses to stay in, or if you could afford it, small chalets to rent. Life, Denis used to say, was both happy and fulfilling in those pre-war days, and Whitelawns was to be their sanctuary, where they planned to live happily ever after.

This was the story of my family’s past I grew up believing. The broad outline of Denis’s early life was told to we three children in dribs and drabs over many years. Denis was a man of the present, his early life only spoken of when pressed, or on the rare occasions when a reflective mood overcame him. It was to be decades later that I came to realise that his stories of his and my mother’s early life were much more fiction than fact.

By 1941, with Britain and most of Europe at war, life began to change at Whitelawns. The privileged self-indulgent life style of colonial living was to abruptly end. The horror of the war could no longer be ignored. In the East, Japan was looking to obtain much-needed commodities that could not be produced at home, expanding her boundaries and eying off the rich pickings to be had in countries beyond her existing borders.

By July 1941, the Western powers had effectively halted trade with Japan. From then on, as the desperate Japanese schemed to seize the oil and mineral-rich East Indies and South-East Asia, a Pacific war was virtually inevitable.

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked British, Dutch and American holdings with near simultaneous offensives across South-East Asia and the Central Pacific, including an attack on the American naval base of Pearl Harbor. The war in the Pacific had begun.

My family, living a mainly sheltered life in the supposed safety of Fortress Singapore, may have believed that their home was a safe haven, but history had other plans for them.

It’s time now to move to the turbulence of the Japanese invasion. A time when circumstances presented my parents with an opportunity to change their lives. It is early 1942 on the small but strategically significant island of Singapore. From here on, fact and fiction join hands and walk side by side into my family’s future.

Chapter 4

Just 70 days, 1942

The dogs of war were baying in the East. By 1942, after five years of bloodshed in Asia, and two and a half years of bitter fighting in Europe, what was to come would be the largest armed conflict the world had ever seen.

On the day that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, its forces also landed at Kota Bahru on the eastern coast of Malaya. Japan invaded Malaya to get control of its valuable natural resources. Japan also saw that the small island of Singapore, at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, would make a strategic launch pad against other Allied interests in the area. With the invasion of Malaya, came one of Britain’s worst defeats of the War — the surrender of Singapore.

Miscalculation, poor planning, and the sheer pig-headedness of some of the decision-makers of the time, contributed to the island’s dramatic capture by the Japanese. It was unthinkable, so the authorities of the day said, that the Japanese could penetrate the Malay jungle and reach the causeway linking Singapore to the mainland. But come they did, on foot, on bicycles and in light tanks — and in double quick time.

Speed was of the essence for the Japanese, never allowing the British forces time to regroup. Land defence operations were not helped by frequent changes of command at almost every level. Errors in retreat by Allied troops, such as leaving useful equipment like barges and motor transport intact and the premature evacuation of some strong defensive positions, all contributed to the success of the Japanese invasion. The advantage of surprise, and having well-trained and well-disciplined troops with an unrelenting determination to succeed at all costs, brought the Japanese to the very doorstep of Britain’s so-called impregnable fortress, the island of Singapore.

The British had confidently predicted that, if the Japanese sought to take Singapore, the attack would come from the sea. That was why all the shore defences on Singapore pointed out to sea. It was inconceivable to British military planners that the island could be attacked any other way — least of all through the jungle and mangrove swamps of the Malay Peninsula. But this was exactly the route the Japanese took.

Nothing had been done to improve the landward defences of the Island. While the claim that the guns could not be turned to face the landward approaches was untrue, both the trajectory and the ammunition type — for weapons intended to engage ships — limited their effectiveness. The British military command in Singapore still believed that war was fought ‘by the rule book’. Social life was important in Singapore and the Raffles Hotel and Singapore Club were important social centres frequented by officers. An air of complacency had developed regarding how strong the Singapore defences were — especially if it was attacked by the Japanese, who many at the time thought to be poor fighters.

At sunset on 8 February, the Japanese attacked across the Johor Strait. The first troops swarmed ashore at 8.54 pm, and over the next 60 minutes, wave after wave of Japanese troops landed their barges on the muddy mangrove swamps of Singapore. The Allied soldiers were too thinly spread to stop the Japanese onslaught. A determined 23,000 Japanese soldiers broke through the under-manned defences and swept onto the Island. They advanced towards the city with speed and ferocity. On 12 February, General H. Gordon Bennett, the Australian commander, began moving his near-exhausted 8th Division AIF units into a perimeter just a few kilometres out of the city. By the next day the Japanese were within 5 kilometres of the Singapore waterfront. The entire city was now within range of the Japanese artillery.

Until this time, the civilian population had been unaware of the dreadful danger they were in. Having been fed the official line that Singapore was secure, which was broadcast through the airways and in the local papers, they were totally unprepared for what was to come. The death toll was rising almost hourly, but rigid military censorship suppressed the truth in the local media. For the preceding two weeks, army censors had even enforced a ban on the word ‘siege’. Using the word ‘siege’, newsmen were told, was ‘bad for morale’.

Official evacuations from Singapore did not even begin until late January and were to continue until the moment of surrender. Even then, under cover of darkness, small boats filled with desperate people would hide among the islands outside the harbour mouth and try to make a run for safety. It was obvious that the city could not defend itself against the invaders. Over the last few days, there had been a concerted effort to get any remaining European civilian women and children out of Singapore. But there were too many of them and too few ships to take them.

In the early hours of 12 February 1942, the last main convoy of ships left Singapore.

Although Churchill had instructed Allied troops to ‘fight on among the ruins of Singapore City’, there was concern about the potential for huge loss of civilian life if the fighting entered the city proper. As it was, artillery and air bombardment were causing horrific casualties among the trapped civilian population. There had been no proper bomb shelters constructed in the city so the population had to make do with sandbagged trenches and under-street drains.

By 14 February, the Japanese had captured Singapore’s reservoirs and pumping stations. The bombing, fighting and heavy shelling continued; many of the Allied troops, separated from their units, wandered around aimlessly and the hospitals were overflowing. Some troops were even deserting and others had become separated from t

heir units. Hard fighting continued, but on 15 February, General Edgar Percival, the British commander in Singapore, called for a ceasefire and made the difficult decision to surrender. He sent a deputation to talk terms to the enemy. The Japanese, however, were in no mood to compromise and demanded unconditional surrender. Percival signed the surrender document that evening at the Ford factory on Bukit Timah Road.

All British Empire troops were to lay down their arms at 8.30 that night. More than 100,000 troops became prisoners of war and hundreds of civilians were interned. At 10.30 that night, the fighting stopped. Singapore had fallen and the Japanese occupation had begun.

It had taken the Japanese just 70 days to crush the British Empire forces in Singapore and Malaya. Just 70 days to bring Singapore to its knees.

Chapter 5

Last man aboard, 1942

During my childhood, and even into adulthood, the ‘Singapore Stories’, including the family’s dramatic escape in 1942, were just some of the many narratives that were to become the tapestry of my parents’ past. The warp and weft of Denis’s stories were woven together expanding slowly over time to create a family history. Told sometimes in monochrome, sometimes in technicolour, the stories always breathed danger, urgency and drama. In later years, my brother Derek developed these stories further giving them more colour and texture, fleshing out and, I suspect, putting his own interpretation on the details. I cannot vouch for the truth of what is written next, just that it is an amalgam of the stories I best remember, both Denis and Derek’s. Yet, my parents and brothers did survive the fall of Singapore, they did arrive at the port of Fremantle on the MV Empire Star in late February 1942 and they did find refuge in their new, adopted country, Australia. The people and the settings in this chapter are certainly real; but the story of the last man aboard may, or may not, be correct in every detail.

Whatever Remains

Whatever Remains